There’s something indescribable about holding your father’s hand as he returns to his Maker. You feel his pulse dissipate, his chest rise and fall slower, then slower yet, and watch helplessly as he takes his final breath.

On Friday, March 28 at 10:45 am Chicago time, on the final Jummah of Ramadan 2025, my dear father returned to his Creator.

إِنَّا لِلّهِ وَإِنَّـا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعونَ

On Sunday March 30, the final day of Ramadan, we held his Janaza (funeral).

My father died in the comfort of his own home, as his four children held him tightly, counting every last heartbeat, every last breath.

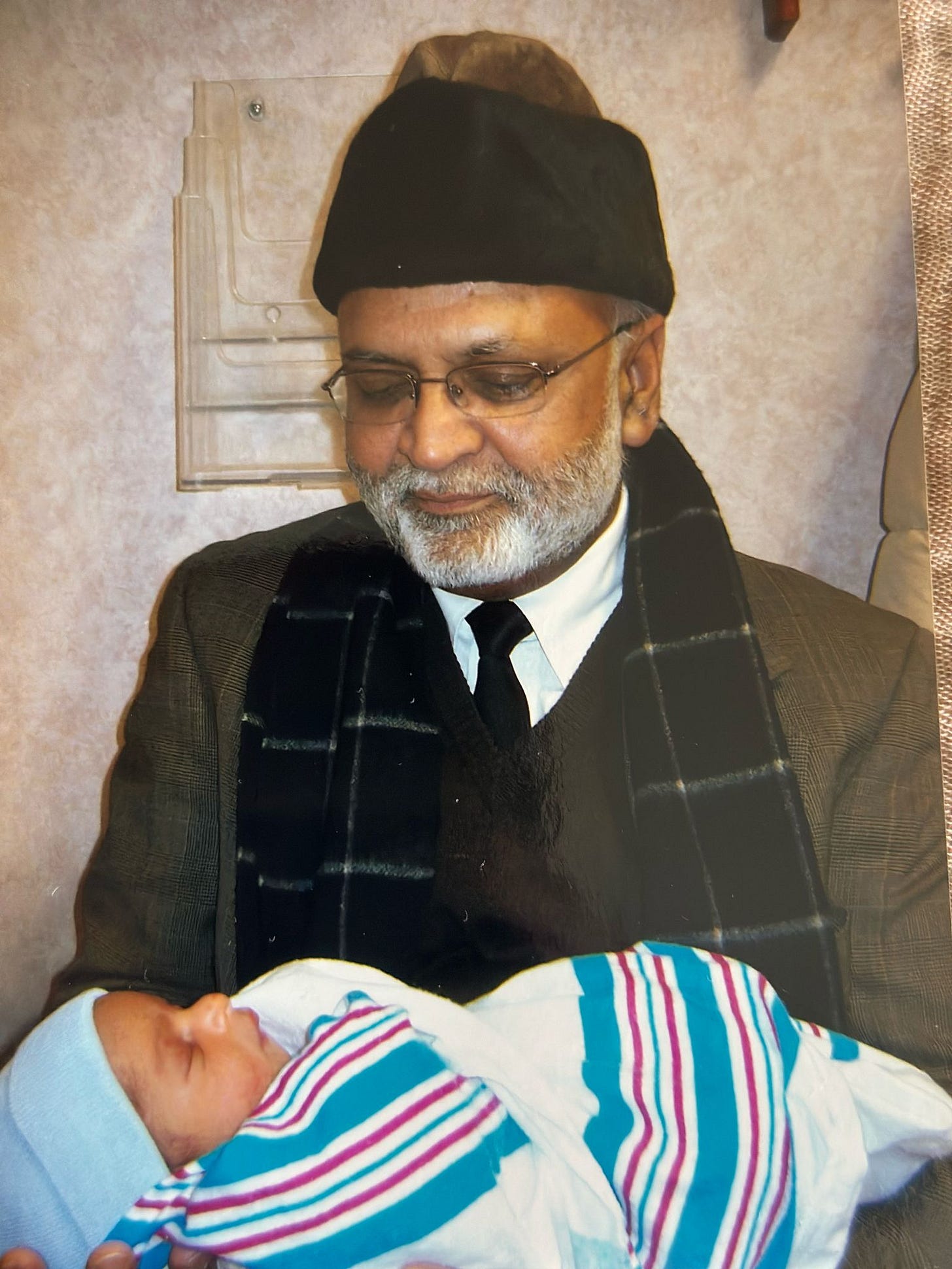

He died while his 11 beautiful grandchildren, ranging from 2 years to 18 years, looking on longingly.

He died while his sisters, nieces, nephews, and daughters in-law sat nearby and prayed for him, as he slipped away.

He died surrounded by love, prayers, by warmth, and with the knowledge that he completed his life’s purpose, passed his test, and that it was time to return home.

The Holy Qu’ran, which is the final holy book for Muslims, teaches us that ultimately this life is temporary and a trial, and that every human being will one day return to the Almighty who created us. The Qur’an declares in Chapter 2, Verse 29:

How can you disbelieve in Allah? When you were without life, He gave you life, and then He will cause you to die, then restore you to life, and then to Him shall you be made to return.

The Qur’an goes on to teach us the Arabic prayer to recite when someone dies as إِنَّا لِلّهِ وَإِنَّـا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعونَ which roughly translates to “To God we belong and to God must we return.”

I cannot possibly do justice to my father’s prolific life and service in one article, nor will I try. Instead, I’d like to share a few anecdotes that exemplify who he was, what he stood for, and what legacy he leaves behind.

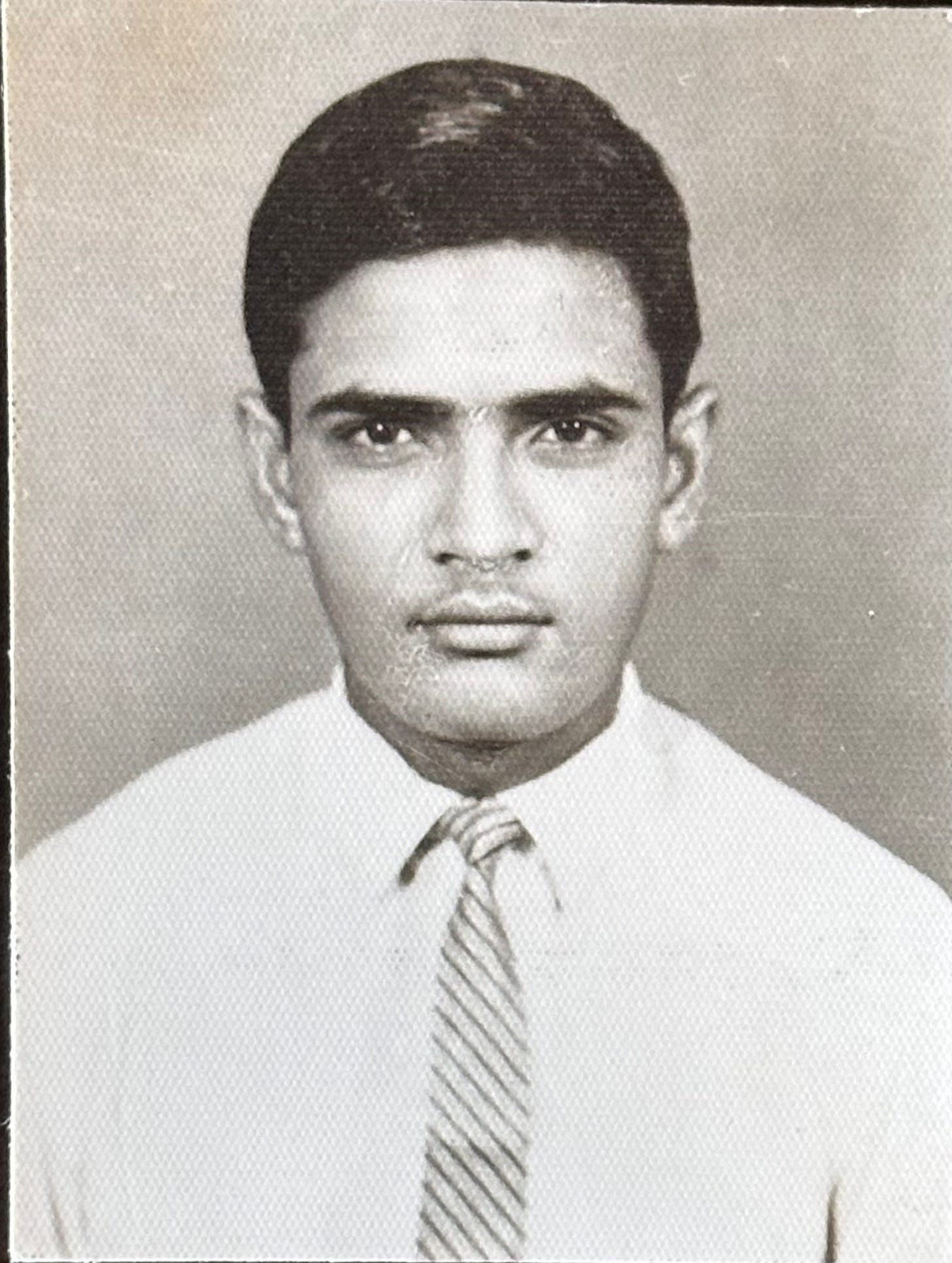

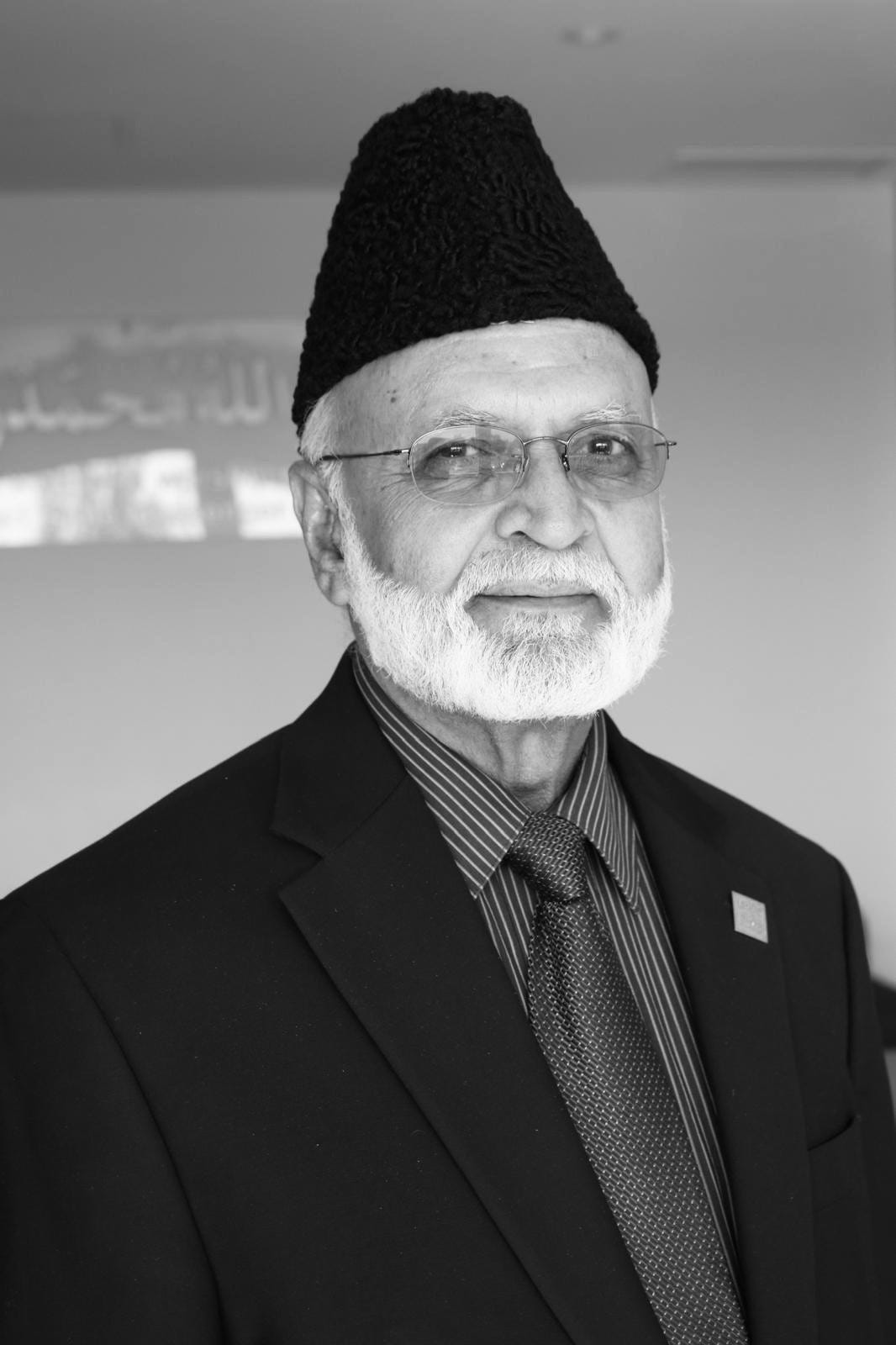

This is Maulana Abdur Rashid Yahya.

Who He Was

Servant, scholar, leader, author, orator, Imam, linguist, professor, judge, world traveler, health enthusiast, fashion aficionado, husband, father to four, and grandfather to 11 — that was my father, Maulana Abdur Rashid Yahya.

Maulana Abdur Rashid Yahya was born on June 19, 1950 as the eighth of nine children, in a small village known as Muradwal in the Punjab region of Pakistan. He was born during the holy month of Ramadan, on the third day. His father, my grandfather Mian Sirajuddin, was a school principal and scholar—a man who spent 15 years studying faith before choosing to affirmatively accept Islam and join in particular the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Muradwal in 1950 was not much different than Muradwal in 2025. While a few homes now have electricity, the village has no paved roads, no plumbing infrastructure, and no real revenue aside from minor farming and agriculture. How did an infant born to a rural middle class family in the agricultural regions of Pakistan, a nation then only 3 years old, live a life that took him around the world? From Pakistan to the United States, the United Kingdom and the UAE, South Korea and South Africa, Guatemala and Germany, Lesotho and Botswana, Mecca and Medina, Rabwah and Qadian, New York and North York, Hamilton and Harrisburg, Mozambique and Manchester, Southfields London, and the South side of Chicago, and the list yet continues?

My grandfather raised my father with the intention of dedicating his son’s life as a servant of humanity. Accordingly, after completing his high school education and his Bachelors, my father gained admission to Jamia Ahmadiyya in Rabwah, Pakistan—a 7-year Islamic seminary. Here, he would gain a scholarly command of Arabic, Urdu, and English, and a deep knowledge of Persian/Farsi. He would complete the intense 7-year study in only 6 years, and still graduate at the top of his class in 1975. A year later he and my late mother, Tahira Rashid, were wed in April of 1976. They welcomed their first child, my elder brother, in February of 1977. Tragedy struck when only 13 days later, my grandfather passed away while my father was a young man of 26.

My father was rarely emotional, but even into the final years of his life when he would speak of his own father, his eyes would well up with tears because he missed him. (Despite the pain I feel in losing my father, I take comfort in knowing that nearly a half century later my father is reunited with his own father).

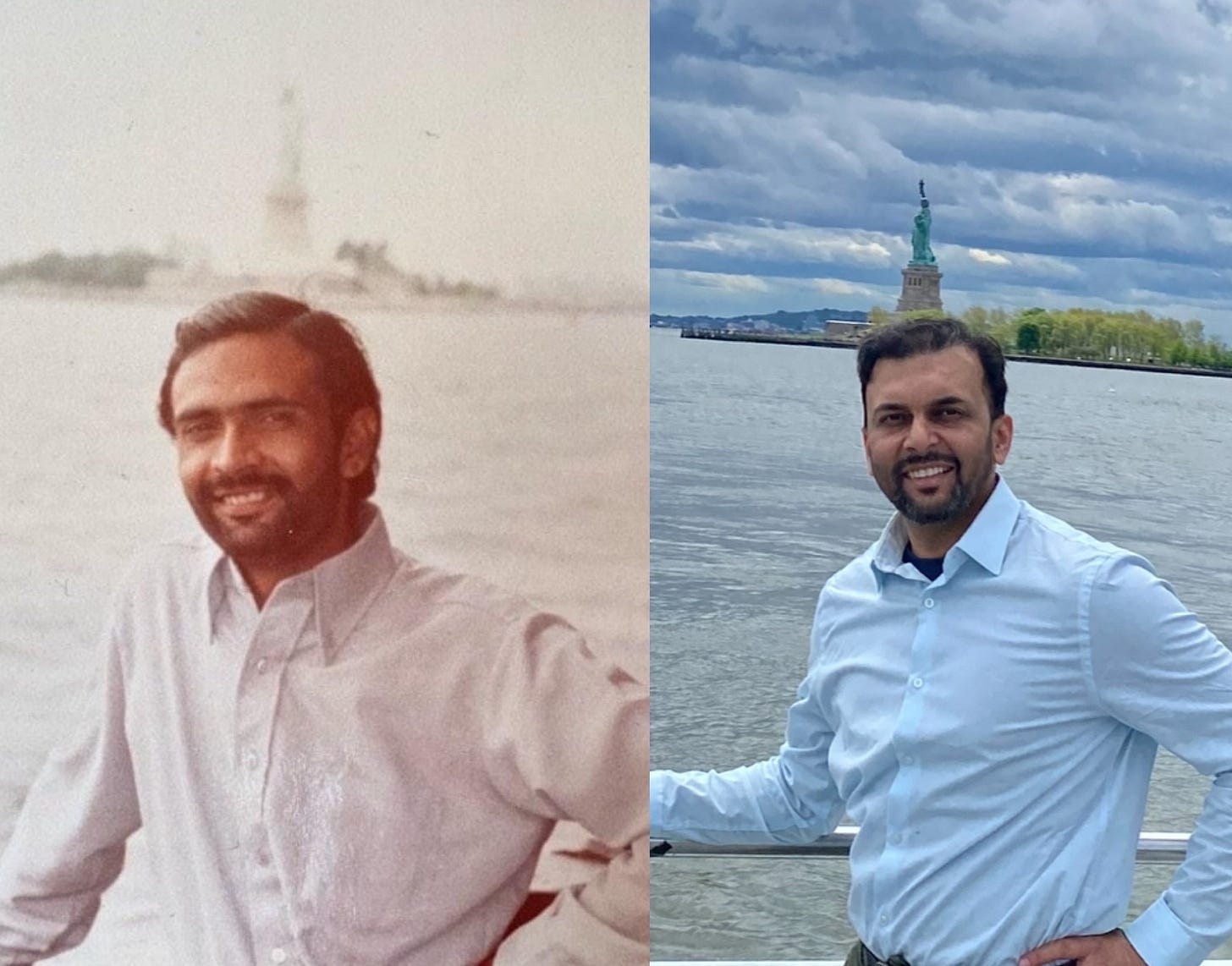

But in those 13 days, before my grandfather’s passing, something else happened. That infant born in the remote hamlet of Muradwal was appointed by the then third Khalifa of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community to travel to the United States of America as an Imam and Islamic scholar. My grandfather died knowing his youngest son would carry on his legacy of scholarship and service to humanity on a global scale. My father thus patiently bore the loss of his father, remained committed to his mission, and entrusted my mother and his first born to his family and to the Almighty. With that, he departed Pakistan and soon arrived in the United States. In this iconic 1977 photo he stands on a ferry with the Statue of Liberty behind him (which I tried to recreate in 2023).

He would not return to Pakistan for more than four years. When we were children he would tell us how even calling my mother from the United States required scheduling a long-distance international phone call a week in advance, and at a cost of roughly $5 per minute—which in today’s terms would be almost $26 per minute. I cannot imagine the level of sacrifice, patience, and commitment he imbibed to relentlessly continue his work—separated by oceans and continents from his wife, child, mother, and siblings. It was this ardent dedication to education, to service, and to fulfilling his promise to his own father that carried my father through his next nearly 50 years of service before his deteriorating health prevented him from continuing his work.

It was this commitment that took him all over the world, where he left his mark with service in Pakistan, the United States, South Korea, South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, Mozambique, Guatemala, and Canada.

It was all driven by what he stood for.

What He Stood For

Though my father was an Islamic scholar and professor who taught doctorate and post-doctorate level classes on Qur’anic hermeneutics, Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali, and Jafaari jurisprudence, and split-word Arabic translation of the Qur’an—my siblings and I were never indoctrinated with any form of religious compulsion. Though he was resolute on praying five times a day, reciting the Holy Qur’an every morning at least, and offering Tahujjed (voluntary) prayer each night—my siblings and I were never forced to pray. And though he generously donated more than 10% of his meagre income to charity—my siblings and I were never* forced to donate our incomes to charity once we started working.

On the contrary, when I questioned my faith as a teen, he not only encouraged me to study the Holy Qur’an and read engrossing books like The Philosophy of the Teachings of Islam, he just as adamantly encouraged me to study other religions, attend other services, and read books by scholars and writers of different faiths (and no faith). My father, Maulana Abdur Rashid Yahya, the Islamic scholar, is why I took the time to read books by Christian apologists Lee Stroble, Paul E. Miller, and Dr. Philip Jenkins, new atheist writers Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitches, and Sam Harris, and a variety of orthodox Muslim scholars, among scholars of other religions. My father is why I visited Hindu temples, Jewish Synagogues, and a host of other houses of worship belonging to different faiths. He is why I’ve read the Gospels cover to cover numerous times, the Torah and the Vedas, Kitab al-Aqdas, and the Book of Mormon.

My father understood that faith is personal between a person and Allah the Creator. That the Qur’anic commandment “There shall be no compulsion in religion” (2:257) was not a suggestion to be considered, but a sacred protection of freedom of conscience to be honored for all humanity. He believed, as I now do too, that when I stand before the Almighty, I will be asked about the choices I made, and why I chose to believe what I believe—and answering “because my father told me to believe that,” won’t cut it. Perhaps the greatest gift my father ever gave me was that rather than teaching me what to think blindly, he pushed me to learn how to think critically.

Thus, on all things related to matters of faith he simply led by example, taught us how Islam’s founder Prophet Muhammad (sa) practiced and exemplified Islam, and let us come to our own conclusions. “Your grandfather studied faith for 15 years before formally accepting Islam and choosing to join the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community,” my father would remind us, “With that living example in front of me, how can I force faith on any of my children?” This, in a nutshell, was my father’s frame of reference on matters of faith.

On matters of service to humanity, however, none of the above seemed to apply.

Service to humanity was not an option. It was an order. As ferociously as he protected us from religious indoctrination, he unrelentingly infused in us the need to serve all humanity regardless of faith, color, or creed. “I don’t care who the person is, what religion they follow or don’t follow, where they are from, or even if they mistreat you, never miss the opportunity to serve humanity. You should be so focused on serving all humanity that your only question should be—did I fulfill my obligation to my neighbor in need?”

This was his response to every complaint we made, as young kids often do, when it was time to do the hard work—whether it was feeding the hungry, raising funds for the less fortunate including out of our own pockets, or cleaning up trash on the side of a busy highway. Above I wrote an asterisk next to “never” when addressing charitable donations. While my father never forced us to donate to charity, he incessantly reminded us that this was a matter of faith and trust in God, that He would increase our incomes if we donated to the less fortunate. And it was a matter of service to humanity as direct financial donations are among, if not the, most practical means to elevate the less fortunate.

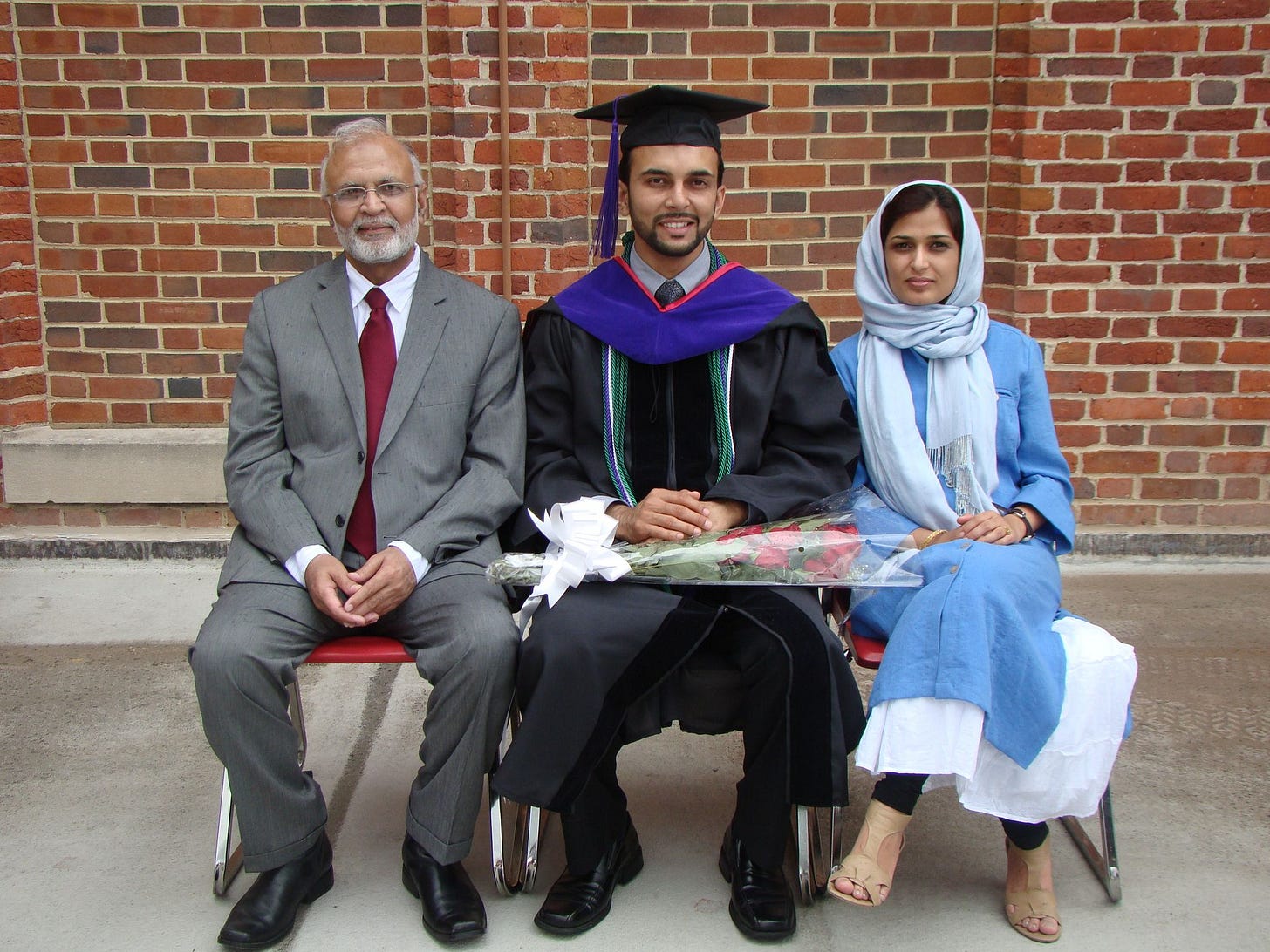

Thus, the only indoctrination my siblings and I received growing up was to relentlessly stand for justice for any and every marginalized community. I can pinpoint this lesson as among my chief inspirations to pursue a law degree and practice human rights law. It’s why I skipped my senior year mid-terms in college to travel to Louisiana to provide support to Katrina victims in 2005, and why I traveled to Turkey, Lahaina, and LA in 2023 and 2024 to support earthquake victims and fire victims, respectively. Service to all humanity is what my father stood for and that is the legacy he leaves behind.

The Legacy He Leaves Behind

Everything I am today, I owe to my father. I see a man who never lived a life of luxury, yet was wealthy beyond comprehension. In his final months, before he lost his ability to speak, a nurse asked him if he had any regrets in life? He responded with conviction, “None. I consider myself more fortunate than the world’s wealthiest billionaires. I have lived a wonderful life, and if this is what God has in store for me as my final chapter, then I am content with His will knowing I did everything I could with what He gave me.” Even in his final days before lost consciousness I would ask him how he was doing, and despite the pain he endured, his only response was to whisper with what little strength he had, “Alhumdolillah,” i.e. God be praised.

I see a man who struggled with health issues throughout his life, yet never made excuses to delay his work. He suffered Rheumatic fever as a child, which left permanent scarring on his heart. He broke both collar bones in accidents. He endured emergency gall bladder surgery. He endured cataract surgery. He endured major oral reconstructive surgery. He endured double heart valve replacement open heart surgery, caused by the deteriorative effects of Rheumatic fever decades prior. And finally, he suffered debilitating PSP, which is a rare form of incurable and untreatable Parkinson’s, a neurological disease that finally took his life.

Despite it all, he endured.

His life exemplifies to me the power of faith in God and quite simply, the power of conviction despite obstacles. As I look at the world today and see what are seemingly insurmountable obstacles and injustices, I reflect on my father’s example of a man who, without worldly means, remained unrelenting in his work to do what is right. And in doing so, throughout his life he advanced the causes of justice and humanity by educating tens of thousands, raising tens of millions in funds for the less fortunate, and raising four children, 11 grandchildren, and dozens of nephews and nieces committed to the relentless pursuit of service to all humanity.

Love of the Almighty, and love of service to all humanity. That is my father’s legacy, and that is how I shall always remember him.

A Smile Is Charity

And through all his struggles, my father loved to laugh. His cackle was distinct, joyous, and infectious. I recall sharing with him a quote from Mark Twain who wrote:

When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.

My father’s subsequent laughter is one I will never forget. And his laughter was surpassed only by his sharp whit. I recall the day my eldest son, now 16, was born. I turned to my father on the drive home from the hospital to say, “I’m cherishing today, and likewise, I can’t wait until he’s old enough that I can hold a conversation with him. Abbu, at what age can you really start to have those dialogues where you can reason with your children?”

As soon as I spoke I bit my tongue, but my father pounced like a lion on its prey, smiling as he responded, “Reason with your kids? I’ll let you know when it happens, son.” I could only chuckle and concede, “Well played, grandpa. Well played.”

Again, as we struggle through the difficulties of contemporary life, I’m reminded of my father’s example to remember to smile and laugh with your loved ones. As Prophet Muhammad (sa) taught, “Even a smile is charity.”

Closing Thoughts…For Now

As I mentioned, no one article can do justice to my father’s life, so I will be sure to revisit life lessons from him in the future. For now I close with the final lesson my father taught me—the precious value of the time we have.

My father was an enemy to apathy and an ardent opponent of procrastination. He cherished every moment he had, and it was impossible to find him wasting his time or anyone else’s time.

His emphasis on time made me reflect on this fact.

In the religion of Islam, the Adhaan (call to prayer) is recited in your ear when you’re born—but there’s no prayer offered. Likewise, a funeral prayer is offered at your death—but there’s no Adhaan to announce that prayer. From that perspective, the Adhaan at your birth is for the prayer at your death.

In our actual five daily prayers, once the Adhaan is called, everyone who hears it understands that the prayer will begin in just a few moments, so be ready to stand before the Almighty. And thus is how we are called to view life. The time between the Adhaan at our birth, and the funeral prayer at our death, may stretch 74 years 9 months, and 9 days as it did for my father. Or, it may be the blink of an eye, as it was for my father’s 84-year-old sister who remembers the day he was born, and wept as she saw him breathe his last. She lamented to me behind a waterfall of tears, “My little brother was just born—how his he already gone?”

For Muslims this is a constant reminder that life is too short to worry about petty things or worse, to harm others. It is a reminder that instead, we must spend our short lives and the precious moments we have in service to one another. That we must be relentless in our service, as indeed that is the only true religion—indiscriminate service to all humanity.

Everything I am, I owe to Maulana Abdur Rashid Yahya. His love and prayers, his mentoring and guidance, his compassion and conviction, his good looks and charming personality, and his unassailable ability to lead by example—qualities that have left an everlasting mark on my heart and mind.

Thank you to the literally thousands of readers, friends, supporters, subscribers, and strangers who have taken the time to send me your notes of love and support and prayers. I do not have the capacity to respond to each person individually, but I have made it a priority to read each comment—please know you have my gratitude. Many have asked how they can offer their support. I can only conclude with the lessons I learned from my father.

If you pray, say a prayer. And whether you pray or not, consider making a charitable contribution to Humanity First USA—my father’s favorite charity—to combat hunger, blindness, and poverty.

Indeed, whatever our differentiating factors, let us remain united on the one true religion—service to all humanity. Nothing would have made my father more proud.

I am so very sorry for your loss. He sounds like a wonderful father and a light in the world. To love and be loved by such a man is a blessing. Peace to you and your family.

Beautiful tribute - thank you for sharing … I lost my dad in 2019 and I miss him every day - that kind of love is a gift.